The media today seems to get a thrill out of announcing that war is around the corner in the Arctic. But 75 years ago, the icebound region really was wracked by battles and bombings. The deserts of north Africa, the jungles of Southeast Asia, and the cities of Europe are commonly imagined as World War II battlegrounds. But the frozen lands and waters of the Arctic were, too.

Actual battles in the Arctic made headlines every so often, with newspapers telling readers in places like Spokane, Washington and Bend, Oregon of ships lost and men saved in frigid climates. On this Memorial Day, here are five such news stories that capture a time when the Arctic made news not because of climate change or resource bonanzas, but rather because of war. In the 1940s, the Arctic represented not a hope for humanity as the last pristine, untouched place on Earth, as it does today. Instead, it showed just how far humans would go to try to destroy the enemy: literally, to the edge of the world.

March 1940

In the 1940s, cod liver oil – “bottled sunshine” – was a common supplement provided by American parents to their children. So naturally, a potential shortage of cod liver, much of it sourced from Norway at the time, could cause a real problem for “Junior,” as the Kentucky New Era worried. Eleven days prior to this newspaper article, the Nazis had invaded Norway and Denmark. A little less than a year later, British commandos taking part in Operation Claymore would raid the Lofoten Islands, the Arctic archipelago in northern Norway that produced some 50% of the country’s fish oil.

The Lofoten Islands were strategic for the Nazis, as they sourced glycerin from fish oil to make explosives. In their surprise raid, the British burned thousands of gallons of fish oil, causing thick, black plumes of smoke to choke the skies. With pristine imaginings of the Lofoten Islands drawing thousands of tourists each year nowadays, it’s hard to imagine such fiery scenes as depicted below unfolding in the recent past. On the other hand, cod is still everywhere on the island – hanging on wooden racks to dry, being sold in the supermarket, and being served up to eat.

December 1940

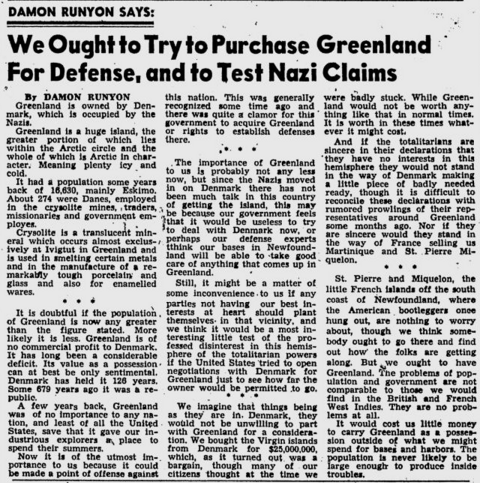

Early on, before the U.S. had even entered the war, American commentators like Damon Runyon of Florida’s St. Petersburg Times were urging the U.S. to purchase Greenland from Denmark. After all, as Runyon argued, “Greenland is of no commercial profit to Denmark. It has long been a considerable deficit. Its value as a possession can at best be only sentimental.” Underscoring his dismissive view towards the world’s largest island, he continued, “A few years back, Greenland was of no importance to any nation, save that it gave our industrious explorers a place to spend their summers.”

A few years after the war, the U.S. offered Denmark $100 million to purchase Greenland. The kingdom refused the offer even though it would have been a massive financial boon, as one blogger has calculated. Why? As noted by the blogger, Danish Prime Minister Hans Hedtoft explained at the time, “Why not sell Greenland? Because it would not be in accordance with our honor and conscience to sell Greenland.” Thus, Runyon was correct in saying that Greenland’s value to Denmark was largely sentimental. But he underestimated the value of that sentimentality to the Danish Kingdom.

Similarly, in his op-ed, Runyon also raised the idea of buying St. Pierre and Miquelon, the two small islands near Canada, from the French. Yet that hasn’t come to fruition, perhaps for reasons of sentimentality as well. Nearly 80 years later, Macron, and not Trump or Trudeau, is the head of state for the 6,000-odd people residing on these two islands off Newfoundland who use the euro rather than the dollar or the loonie.

March 1942

In the late winter and early spring of 1942, there were fears that the Nazis would attack U.S.-protected Iceland. Since August 1941, Allied convoys had sailed from naval bases in Hvalfjörður and Reykjavik in Iceland to northern Soviet ports, generally Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Hvalfjörður is pretty quiet today, though it is home to Iceland’s last remaining whaling station (the name itself means “whale-fjord” in Icelandic). I once accidentally close to an hour driving around the whole fjord rather after missing the shortcut (an underwater tunnel opened in 1998 that takes about 7 minutes to drive through.) Arkhangelsk, too, is now a pleasant coastal city in the Russian Arctic where people play beach volleyball during the long summer days.

May 1942

In spring of 1942, Tirpitz’s supposed raid on Iceland still hadn’t materialized. The Western Allies continued sending ships from posts in the North Atlantic to help send vital supplies to the Soviet Union. In April, Allied Convoy PQ 15 set forth from Reykjavik, bound for Murmansk. Nazi raids sunk three of the 25 ships in the convoy, but the others managed to safely reach their destination. It was difficult to travel covertly in the Arctic in summer due not to ice, but rather to the persistent daylight that made it impossible to hide under the cover of night.

September 1943

During World War II, the Germans bombed Allied positions on the island of Spitsbergen, within the Svalbard archipelago, with the aim of destroying “military establishments, coal mines and ports”. While unknown at the time by The Spokesman-Review, German battleships Tirpitz – the very one that was once feared to be on its way to striking Iceland – and Scharnhorst carried out the attacks.

Today, Svalbard is now a place for global science and polar bear sight-seeing. It’s even home to the Global Seed Vault – the last repository for the world’s seeds – partly by virtue of it now being deemed one of the safest, most secure places on Earth. Nazis may no longer threaten Svalbard, but earlier this month, the entrance to the Global Seed Vault unexpectedly flooded after a spate of warm temperatures. The biggest threat to Svalbard now may be one for which anyone who has ever emitted greenhouse gases bears some partial responsibility: climate change.