Yesterday, the Obama administration conditionally approved Shell’s exploration plans this summer in the Chukchi Sea, off Alaska. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s decision is available here. Many environmentalists lambasted the president’s decision. The Guardian quoted a representative of Oceana, an oceans advocacy non-profit, as saying that an Arctic oil spill could have “catastrophic effects on the area’s wildlife and devastate one of the last intact marine ecosystems in the world.” Environmentalists are right to worry about drilling in the Arctic. Oil spill response plans are lacking in readiness, for there’s hardly any infrastructure around (more on that later). Oil breaks down slowly in the Arctic’s cool waters, and Shell already has a worrisome record so far in the Alaskan offshore as profiled by the New York Times in their feature magazine story, The Wreck of the Kulluk, last December. Yet environmentalists and many others are misguided in their perception of the Arctic as a pristine environment. The World Economic Forum introduces their document, Demystifying the Arctic, with the following paragraph:

“To this day, the general public thinks of the Arctic in visions of unspoiled ocean and landscapes, expansive ice, clean water, unique species and aboriginal cultures – essentially, it reminds everyone that a true wilderness still exists.”

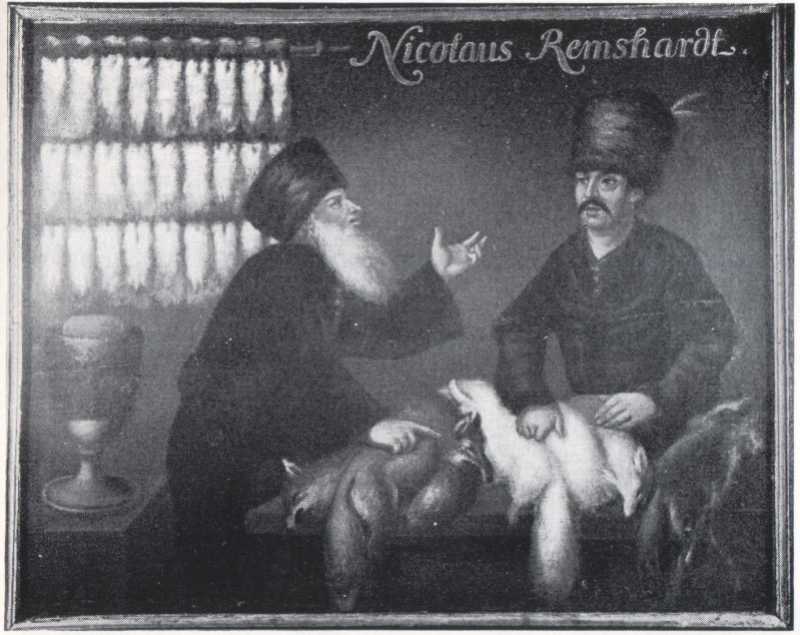

Nowhere in this document that is supposed to “demystify” the Arctic is there a discussion of previous ruinations of the Arctic’s environment. While the region may not be smoggy like Los Angeles, clear-cut like vast swaths of the Amazon, or slashed and burned like the forests of Southeast Asia, it has been plundered nonetheless. To name just one example, from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries, millions of fur-bearing animals were trapped in the Eurasian and North American Arctic, their pelts sold in markets in places like St. Petersburg, Beijing, and New York. In a single year, the pelts of 70,000 sables, 700,000 ermines, 5 million rabbits, and 15 million squirrels were removed from Siberia. The book Furs and Frontiers of the High North illustrates the vast elimination of furry animals like Arctic fox, sable, mink, squirrels, and otters from the tundra and taiga. Only 150 European Arctic fox are left in the wild, for instance, making them just a little less rare than fur-bearing trout.

The Arctic’s mountains still stand tall while its glaciers glisten blue. Thus, the physical landscape is still more or less intact (though changing rapidly now due to climate change). But many of the small animals that once darted across those lands are gone, victims of rapacious resource extraction driven by consumer demand in the metropolises of the south. The lack of compelling photographs of landscapes before and after the depletion of the Arctic’s animals doesn’t make the changes to the environment any less dramatic, though it does make them harder to represent to the public. If someone has as powerful a visual for illustrating the overhunting of Arctic species as the photographs that document glacial retreat, please feel free to comment.

The frontier goes underground

In the 18th century, Chinese aristocrats were wearing fur coats on the streets of Shanghai and Beijing. While fur may no longer be as fashionable as it once was, at least in much of the Western world, fuel is king in the streets of the West. This leads me to a second point. When the Arctic is posited as a “last frontier” or “new frontier,” such phrases are purely rhetorical devices meant to prime the (re-)opening up of land for capital investment. The fur frontier closed when when tastes for fur fashions dissipated in the middle of the nineteenth century, by which point much of the Arctic’s organic material had been depleted. The next frontier in the Arctic eventually became its inorganic material: the substrate, offshore, in rocks – wherever fossil fuels and minerals might lie. Rather than the Arctic representing a “new frontier,” instead, the frontier has simply gone underground. Capitalism’s expansion is dependent on this type of multidirectional geographic expansion. Since most of the earth’s land has already been incorporated into the web of global trade, expansion is now moving into different volumes, down into the soil and even up into outer space, where various companies hope to one day mine asteroids. Expanding into these challenging areas requires large expenditures that will hopefully result in even larger returns. In an interview with AP, ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson noted, “The size of the resource prize has to be large to support the risked capital that has to be put in place. The Arctic is one of the few places left where we believe those opportunities exist.”

The Arctic needs investment. Why?

More than just being put at risk, capital will also benefit from the construction of new infrastructure in the Arctic since it offers additional opportunities for returns. Once built, new infrastructure will also allow hastened extraction of Arctic resources previously trapped not just by ice, but by a dearth of pipelines, railroads, and ports. Jason Moore, an assistant professor of sociology at Binghamton University (who also runs a fantastic blog called “World-Ecological Imaginations”), writes, “Fresh supplies of land and labor, in turn, are worthless without a reconstruction and expansion of the system’s built environment, especially its transportation networks” [1]. The Arctic may be on the verge of this type of development given politicians’ calls for new infrastructure like ports, ice-strengthened ships, all-weather roads, and the like. All of this infrastructure is necessary to support the extraction of minerals, the commodity on which the current round of Arctic development is largely premised. As such, it should come as no surprise that the World Economic Forum defines “Challenge 2” for the Arctic as, “The Arctic needs investment. A critical deficiency and area of great strategic importance is the development of infrastructure projects and logistical hubs.”

Left unsaid is the reason the Arctic needs precisely this type of investment at precisely this moment. The answer is that the types of commodities that states and investors wish to extract has changed. In previous centuries, there was a whole network of trade routes centered around the fur trade, for instance. Many of the fur trading posts have disappeared, “lost with the deterioration and dismantling of most forts and posts shortly after abandonment,” as the National Park Service website describes. The site continues, “Most of what we know about these sites comes from archeological research.” Whatever infrastructural traces remain of the fur trade are no longer useful, as it is billions of barrels of liquid fossil fuels that must be moved – not small pelts that could be transported by reindeer, boats, and people on horseback. The change in the type of commodity being removed from the Arctic necessitates changes in transportation infrastructure. Pipelines, shipping routes, and railroads are replacing the pathways of previous eras.

The whitewashed frontier

To whitewash the Arctic as a new frontier, there is no shortage of “frontier discourse” by bureaucrats, investors, oil men, and reporters. Here are just a few quotes and examples from the past few days.

- Ahmed Ben Salem, a Paris-based analyst with Oddo & Cie: “The Arctic is the next big frontier.”

- Professor Heather Gautney in The Huffington Post: “U.S. soldiers funded by taxpayer dollars being trained to guard an impending oil and gas rush in the Arctic — a new frontier being pried open by climate change“

- Senator Angus King (I-Maine): “The Arctic is a new frontier.”

- Shell’s drilling rig destined for the Chukchi Sea this summer is called Polar Pioneer.

- Deputy Energy Secretary Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall: “The result of this warming is a new frontier with increasingly accessible resources…Your leadership and cooperation will position us to lead in the Arctic.”

In contrast to Sherwood-Randall’s belief that global warming has brought about the latest round of Arctic exploration, in fact, improvement in technology are driving the push northward and downward of the oil frontier. ExxonMobil CEO Tillerson essentially stated as much in his interview with AP. He remarked, “Anytime you are dealing in these frontier areas where you are really driven by technology, these are very long time frames, multi-decade time frames.” He did not mention climate change as a motivating factor.

Rex Tillerson’s interview is probably one of the most frank interviews I’ve seen lately from someone speaking about Arctic resource extraction. It’s short and worth reading – perhaps most of all because he shamelessly admits, “We are in the depletion business.” Let this be a reminder that once all of the Arctic’s fur-bearing animals were depleted in the nineteenth century, many groups of indigenous people that has once profited from the fur trade became quickly impoverished and lost a great deal of political clout. Should the day come when the Arctic’s fossil fuels have been depleted – even though a recent study in Nature concluded that they must stay in the ground to limit global warming to 2°C – what will be left except impoverished locals and traces of abandoned pipelines and platforms for archaeologists to one day uncover?

Sources

Reblogged this on Dogma and Geopolitics.