Earlier this month, the Wall Street Journal reported that more crude oil is being sent by sea and inland waterways as a supplement to railways and pipelines. Since 2010, the amount of oil shipped on barges from the Midwest down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico has increased 13 times. Much of this oil from the Midwest is coming from fracking in North Dakota’s Bakken Shale and the oil sands in Alberta. Without the Keystone XL pipeline, the oil still has to get to market somehow, so barges are the answer. Companies are seeking out “alternate routes where pipeline’s don’t exist or have sufficient capacity.”

What’s happening in North America is a result of economic necessity: pipelines are full or non-existent, so companies are turning to waterways to move their commodities. In the Arctic, however, oil and gas often has no choice but to move by sea given the region’s watery geography.

In Russia, state-owned oil company Rosneft announced that it will build two shipyard facilities to bolster Russian Arctic hydrocarbon production. Not just ships, but actual shipyards. One facility will be built near Murmansk, in northwestern Russia, and have dual military-civilian shipbuilding capabilities. The second facility will involve upgrading the existing Zvezda shipyard some 12 miles north of Vladivostok at the eastern end of the Northern Sea Route so that liquefied natural gas carriers and Arctic drilling platforms will be able to be constructed. This second facility will actually be built by a consortium including Rosneft, Gazprombank, Sovcomflot, and also South Korean company Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering. A statement released by Rosneft’s president in November 2013 announced, “We are convinced the cluster will become a center for high-tech arctic shipbuilding in Russia.” South Korea is literally around the corner from Vladivostok. The country completed its first pilot service of the Northern Sea Route with an oil tanker carrying naphtha in October 2013 with the help of Swedish shipping company Stena Bulk. The consortium in Zvezda exemplifies the new geocommercial realities of the hydrocarbon industry in the Russian Arctic: in a maritime operating environment, Asian technology and investment are helping to extract Russian resources, largely destined for Asian markets.

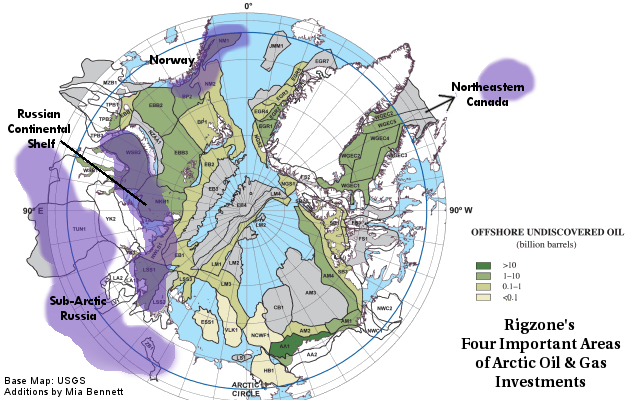

The spending on oil and gas activities in the Russian Arctic continental shelf is one of four regions that Rigzone identifies as investment hotspots. The other three areas that are predicted to witness the greatest forthcoming capital expenditures are Norway, northeastern Canada, and the Russian sub-Arctic. From 2014 to 2018, Norway will see an estimated $3.4 billion in expenditures, northeast Canada $3.2 billion, the Russian sub-Arctic $3.2 billion, and the Russian continental shelf $2.7 billion. In northeast Canada, Norwegian company Statoil recently announced it would increase its exploration activities in Bay du Nord, off the coast of Newfoundland. In total, the spending in these four areas equals $12.5 billion. Especially since it is spread out over four years, this sum is chump change compared to the total $120 billion that Chevron, Exxon, and Shell spent in 2013 alone to increase their output – about the same cost in today’s dollars as it cost to put a man on the moon, as the WSJ claims.

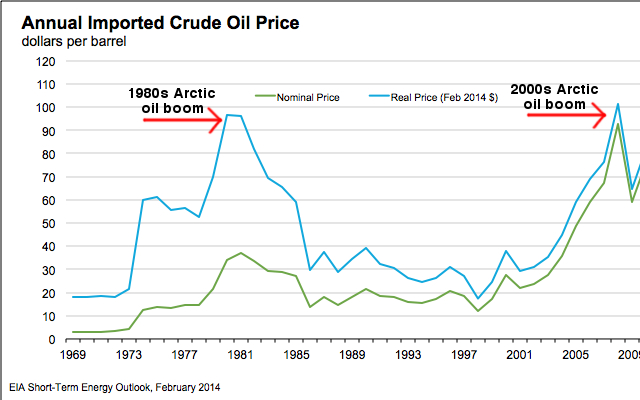

Down the line, the picture for Arctic oil and gas expenditures is not looking so positive for corporations. With the price of oil relatively low and forecast to decline to $90 by the end of the decade, the oil majors are being forced to roll back many of their megaprojects. In a shift from the gung-ho, pre-recession attitudes of oil corporations in 2007, industry experts are now trying to scale down expectations about Arctic activities. At this week’s Arctic Technology Conference in Houston, Texas, Abdel Ghoneim, an engineering manager with Atkins Global, participated on a panel excitedly titled “GLOBAL ARCTIC MARKET OUTLOOK— PUSHING THE FRONTIER!” He tempered the enthusiastic title by explaining that the price of oil will remain the most important factor in determining whether Arctic exploration and production is commercially feasible. Ghoneim reminded the audience that the oil exploration that took place in the Beaufort Sea in the 1980s would have continued had the price of oil not dropped significantly. Thus, it’s not just climate change and increased accessibility that determines activities in the Arctic. Commodity cycles do as well.

Let’s not forget that the courts, at least in the United States, play an important role in determining whether exploration can proceed. On January 22, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that (full ruling here) the government acted in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner in holding a lease sale based on a “one billion barrel estimate of total economically recoverable oil” in the Chukchi Sea off the northwest coast of Alaska. Eight days later, Shell announced that it would not pursue its plans to drill exploration wells in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas this summer. With Shell’s profits having fallen 71% in the fourth quarter or 2013, offshore Alaska will likely remain off the table for some time to come, both in terms of legal and economic feasibility. As the oil moves by ship and barge in the Lower 48 and southern Canada, it will be similarly transported across the ocean in Arctic Russia, where the political and economic climate around oil and gas development is completely different than it is in the U.S.

This post originally appeared on the Foreign Policy Association’s Energy Independence Blog.