Once fixed in place, commodities like diamonds can now be conjured out of the sky from anywhere. This bodes ill for locations in Siberia and Canada’s Northwest Territories that depend on the mining industry.

The other day, I came across an article by commodities correspondent Henry Sanderson in the Financial Times on the quest to manufacture lab-grown diamonds. These are virtually indistinguishable from diamonds that come from the ground. Both are formed thanks to a combination of intense pressures and high temperatures. But whereas natural diamonds take roughly one to three billion years to form (25-75% of the Earth’s current age), a lab-grown diamond can crystallize in just five days.

In the FT article, Dale Vince, the founder of a British green energy company called Ecotricity, offered:

“We no longer need to mine the earth to make diamonds, because we can mine the sky.”

Vince was referring to an alternative diamond-producing technology called chemical vapor disposition used by his company, in which diamonds are created with the help of methane (CH₄) produced using carbon sourced from the atmosphere and hydrogen split off from water molecules. With this technology, diamonds, which are just pure, hardened carbon, can basically be produced anywhere with sufficient energy.

As more diamonds are grown in labs around the world, their price has dropped to a approximately a third less than mined diamonds. In a few years, synthetics might be only 10% the cost of the real thing. The luster of natural diamonds is also wearing off, particularly among Millennials averse to buying gems that might come from warzones or environmentally degraded areas. While Hollywood blockbusters like Blood Diamond (2007) have shone a harsh spotlight on conventional mining, the darker side of lab production—namely its energy-intensive process, which can emit three times more carbon dioxide—has managed to escape scrutiny.

The geography of synthetic diamonds

A market dominated by China

More than half of the world’s manmade diamonds are produced in China. The amount produced in Asia as a whole rises to nearly 80% when India and Singapore are added to the list.

China produced its first synthetic diamond in 1963. Lab production of the extremely hard mineral began for use in aeronautics, oil rigs and electronic chips. In 1989, to direct the growth of the domestic industry, China’s State Planning Commission began planning for the establishment of a “State Key Laboratory of Superhard Materials,” which opened ten years later.

Now, Henan Huanghe Whirlwind, the world’s largest synthetic diamond manufacturer, produces 1.2 billion carats each year. Most of these are still for industrial purposes, but lately, the company has expanded into gem-quality production to capitalize on rising consumer interest in synthetic diamonds. Henan Huanghe Whirlwind’s quest to revolutionize the global diamond industry is captured by the company’s slogan, which turns the mineral from a noun into a verb: “We diamond the world.”

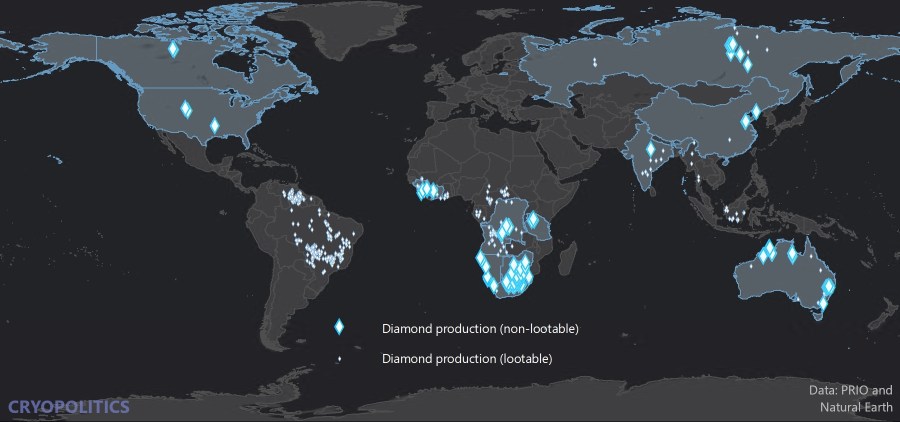

The geography of mined diamonds

The Arctic and southern Africa

Nearly half of the world’s mined diamonds come from Russia and Canada, while another third comes from Botswana, South Africa, and Angola. Nearly all of Russia and Canada’s mines lie high up in the Arctic, where enormous pits have been dug into the frozen tundra over kimberlite pipes: igneous rocks, many of which contain diamonds (referred to as “diamondiferous” by geologists) that rose to the Earth’s surface 100 million years ago from deep in the mantle where the crystals were formed.

In Russia, 98% of the country’s diamonds (representing an astonishing 35% of global production) are mined in the Sakha Republic in eastern Russia. The industry is centered on Mirny City, a Soviet-era monotown where in winter, pink clouds of steam billow over snow-crusted apartment blocks emblazoned with murals depicting the heroes of yesteryear like cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

Russian global mining conglomerate Alrosa, also the world’s largest diamond producer, controls the country’s diamond production. In total in Sakha, mining of diamonds and other commodities, primarily oil and gas and coal, accounted for 44% of gross regional production (GRP) in 2014, according to a PricewaterhouseCooper report on the republic.

Canada’s diamond mining industry has more recent origins. It got its start in the 1990s after a serendipitous discovery of kimberlite pipes in the Northwest Territories by two geologists. While the territory has a more diversified economy than Sakha, mining, involving mostly extraction of diamonds and some oil and gas, still accounts for approximately 20% of gross regional product (GRP).

When the Canadian and Russian industries are added together, diamond mining ends up represents a significant proportion of the Arctic’s GRP.* New technologies and new competitors, specifically Asian countries using advanced engineering rather than nimble mining operators in remote frontiers, therefore could undermine an important pillar of the region’s economy.

The on-the-ground consequences of diamonds from the sky

The impacts of synthetic diamonds will not be felt in corporate boardrooms. DeBeers, for instance, is investing heavily in their design and manufacture, much as oil and gas companies are investing in renewables. Instead, any slowdown to diamond mining will reverberate across the post-Soviet cities and Indigenous settlements dotted across Sakha and the Northwest Territories that have come to depend on the industry.

Mines often rely on labor flown in from southern latitudes, but they also employ local and Indigenous residents. Their revenues and taxes support community infrastructure and programs, too. Diamond mining companies also fund and operate much of the infrastructure that keeps these towns connected to the outside worlds, whether ice roads or airlines. For instance, I was able to fly directly from Moscow to Mirny City with Alrosa’s company airline, which sells tickets to both regular passengers and mine workers.

On the one hand, mines have completely razed diamondiferous Arctic landscapes by punching enormous holes into the tundra over half a mile wide that look ready to swallow up the tiny buildings perched on the horizon. The industry has also upended Indigenous relationships with the land and disturbed and destroyed flora and fauna. In Russia, over the years, hazardous work environments have also caused the death of dozens of miners, most recently in 2017.

On the other, the industry has funneled wealth into the capital of Sakha, Yakutsk, where many people drive second-hand vehicles imported from Japan and fly direct to Thailand and Vietnam for their winter holidays. Diamond mining revenue has helped purchase snow machines and pay for a greenhouse in the Northwest Territories. The costs of such corporate social responsibility initiatives are pocket change to a multibillion dollar industry that is siphoning resources out of the ground in the Arctic. But given that northern economies are now globalized and capitalized and dependent on 24/7 flows of money rather than seasonal migrations of whales and caribou, these benefits are better than nothing.

So what will come next for diamond-dependent northern communities if synthetic production in China and elsewhere makes their production uncompetitive, not to mention undesirable by consumers?

Most likely, the economies of Sakha and the Northwest Territories will go bust. The risk of the obsolescence of an entire industry, not only of diamonds but also perhaps of oil one day in places like Alaska, is all the more reason for northern economies to diversify and invest in high tech and services rather than relying wholly on things in the ground.

It’s raining diamonds

Once fixed in place, now, commodities like diamonds can be conjured out of the sky from anywhere. This radical shift in the geography of natural resources from being place-specific to ubiquitous could reshape not only economics, but geopolitics, too. Imagine a world in which not only diamonds could be manufactured by anyone with the know-how, but rare earth minerals or even oil and gas. It’s an outlandish proposition, but an interesting thought experiment. (For what it’s worth, scientists are looking into obtaining rare earths from the toxic dredges of mining waste.)

If commodities could be produced anywhere with the right mix of technology and energy, would governments still care about controlling access to resource-rich lands and seas? Would Indigenous Peoples still hold the same amount of leverage in land claims negotiations? And, in settling claims with the state, would they seek to gain access to technology rather than resources?

Time will tell.

*I was hoping to do a back-of-the envelope calculation on the proportion of diamond mining within the Arctic’s GRP using the values of $4 billion in revenue for Alrosa in 2018 (which includes all of its mines in Sakha and Arkhangelsk, plus additional revenues from the mines it helps operate in Angola, which would preferably be omitted) and $451 million for the value of diamond mining in the Northwest Territories in 2016. However, the latest statistic I could find for the Arctic’s GDP, $225 billion, is from 2003, and hence quite outdated. If we run the math using these very rough and incomparable figures, though, then diamond mining accounts for 4.7% of the Arctic’s GDP.