In summer above the Arctic Circle, the sun does not set. This phenomenon, generally called the Polar Day, is referred to as “White Nights” in St. Petersburg and much of the Russian North. People across the Arctic welcome the start of the Polar Day with joyful festivities like Midsommar in Sweden or National Day in Greenland. Though St. Petersburg is a bit south of the Arctic Circle, it still experiences the luminous aura of polar summers. Here in Russia’s so-called “Northern Capital”, from late June to late July, people stay up to watch the bridges across the Neva River open to let ships pass, listen to street music, and stroll along canals lined with pastel pink and yellow palaces under the shadow of Peter the Great.

But another shadow looms large across the White Nights, and that is the shadow of forced labor. From 1931-1934 in Soviet Karelia, the republic that lay just to the north of St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), the government took advantage of the lengthy daylight to force 16 to 18-hour work days on the tens of thousands of gulag prisoners who were building the White Sea-Baltic Canal. Work days should only have been seven or eight hours long, but they were instead double that.

Stalin believed that by connecting the White Sea to Lake Onega, which a separate waterway linked to St. Petersburg and the Baltic, Russia’s naval and commercial fleets could access the country’s northern coast without having to sail through the Baltic and around Scandinavia. It would also facilitate connections between Russia’s industrial centers in the southwest to towns and settlements in the Russian Arctic and northern Siberia. With such promise, the canal was naturally a dream of the Soviet dictator.

For the people who worked on it, however, it was a nightmare. They essentially hand dug the waterway with primitive tools and implements. An estimated 12,000-25,000 people died during the canal’s construction, and the workforce mortality rate was 8.7%. (For the Panama Canal, in contrast, where the government took pains to control malaria, the mortality rate was around 4%.) One of the more gruesome rumors about the White Sea-Baltic Canal holds that so many people died, bodies were cemented into the canal walls.

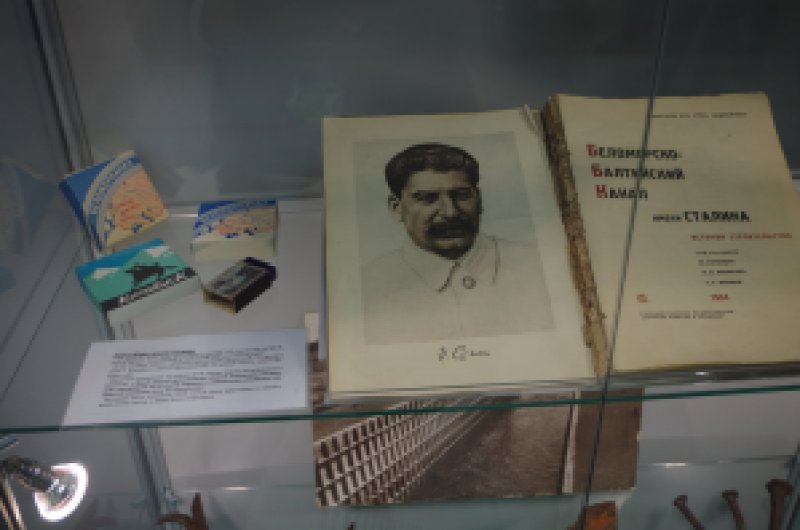

Construction on the 227-kilometer canal finished four months ahead of schedule, and the Soviets heavily advertised it as a manifestation of national work ethic. A cigarette brand called Belomorkanal (which is still produced) and all sorts of other paraphernalia trumpeted the canal’s opening. The canal even originally bore Stalin’s name. But due to its haphazard construction, the shallow canal – 3.5 meters deep at a minimum, where it should have been at least 5.4 meters deep – failed to become the busy thoroughfare between the Arctic and the Baltic that Stalin had hoped. It did lead to the creation of the Soviet Union’s northern naval force: in 1933, two destroyers, two frigates, and two submarines from the Baltic Fleet sailed via the canal to Murmansk. This small flotilla represented both a publicity stunt, as Ziemke writes in his book The Red Army, and the foundation of the Northern Fleet.

Today, the Republic of Karelia is considering revamping the canal in order to attract more tourism, since its shallow waters are more conducive to pleasure craft than cargo ships. Cargo traffic peaked in 1985, with 7.3 million tons transported. In 2002 in contrast, the canal transported a mere 314,600 tons. The canal still serves some economic purpose: all Arctic chemical plants, for instance, are supplied via it. But expanding Stalin’s pet project to allow high levels of commercial shipping is probably out of the question due to the enormous expenses that would be required. The free labor of tens of thousands of prisoners is no longer an option.

We drove by some of the canal locks outside of the city of Medvezhyegorsk, but we were never allowed to exit our bus. This may be due to the fact that the White Sea-Baltic Canal has become more of a security concern in recent years. More enlightening was the city’s Regional Museum, where we had the opportunity to hold actual tools that had been used in digging out the canal.

Later on in our trip, we visited the Solovetsky Islands, which I’ll return to in future posts. On Solovki, one of the first “corrective labor camps” – forerunners to the gulag system – was created. One thing that stuck with me was learning that Solovki formed the ideal prison not just because it was an island in the middle of the forbidding White Sea, but also because in summer, the white nights made it near impossible to escape under cover of dark. Many of the prisoners from the Solovki gulag were forced to work on the White Sea-Baltic Canal. This infrastructure created a waterway of horrors from the Arctic to St. Petersburg, a city supposedly “built on bones” due to the thousands of serfs forced to drain its swamps and erect its palaces.

In sum, two particular aspects of the polar night – the ability to force longer working days and to thwart gulag escapes – put a somber cast on what I had previously thought of as a wondrous, astronomical phenomenon. In the Arctic, nothing is as white and innocent as it seems.

One comment

Northwest Russia: Hard labor, white nights, and a canal